“Stay here! If you walk away, I’ll call for you”, sings Hassan Shakosh to the neighbour’s daughter in his 2019 hit “Bent el-Geran” (The Neighbour’s Daughter). “You’re mine and I’m yours, we’re stuck together. If you leave me, I’ll hate my life. I’ll drown my sorrows in alcohol and smoke hashish.” While the song garnered more than a half-billion views on YouTube alone, its reference to alcohol and hashish became the lightning rod of a culture war that has been raging between Egypt’s self-proclaimed custodians of heritage and the working classes. The culture in question, mahraganat, that hypnotic mix of folk rhythms, electronic synths, high energy autotune-rap, and controversial lyrics, is but a mere era in the debate of what kind of music Egyptians should consume and produce.

“Bent el-Geran”’s alleged vulgarity prompted the Egyptian Musicians Syndicate to ban mahraganat from public spaces in February 2020. This kind of music must not be played on television, radios, or in clubs, they decided. It is vulgar and cheap and it spoils public taste, they said. However, degradation and censorship is nothing new to working class musicians whose songs continue to be celebrated in buses, cars, cafes, restaurants and at weddings and parties all over the country. Since its inception, sha’bi, or “popular music”, and the genres it inspired have become synonymous with the kind of vulgarity that reflects, rather than obscures, modern life and art in Egypt.

A truthfully vulgar soundscape

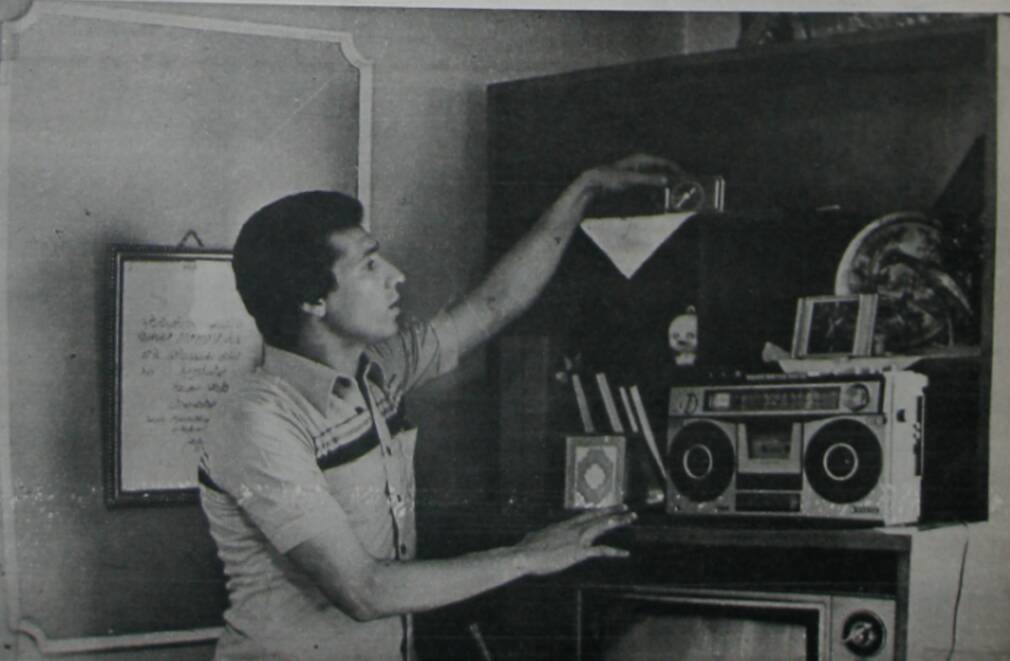

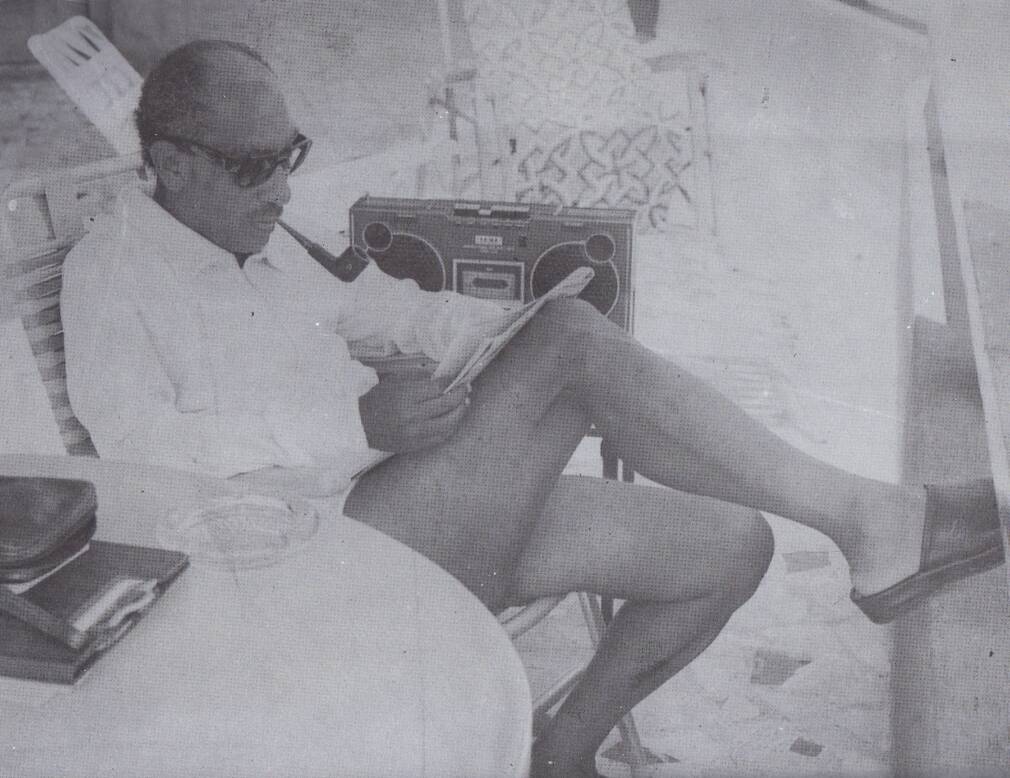

In his book Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt, Andrew Simon traces the social life of cassette tapes, which emerged in Egypt in the 1970s. His research shows that cassette technology enabled an unprecedented number of people to create culture outside the confines of state-controlled media, and to consume music that reflected their realities and experiences more authentically than state-sanctioned high culture. In other words, anyone could press record on a cassette recorder, make a song, and inject their voice into Egypt’s soundscape. The radio might not play it, but inexpensive, small audiocassettes could let it resound in the homes of any class, anywhere around the country. “It was in this transitory climate that audiotapes carrying content cultural gatekeepers considered questionable, most notably shaʿbi (popular) music, became public enemy number one for a wide range of critics who held the everyday technology accountable for poisoning public taste,” writes Simon.

Who gets to decide which music is worth listening to? The endeavour to censor sha’bi, vilified as the “downfall of music” and “the death of taste”, began in the 1980s. Then-President Anwar Sadat issued a series of decrees that made “noisy” cassette recordings illegal; radio stations were tasked with “molding model citizens” by way of elevating refined musicians, such as Umm Kulthum and Abdel-Halim Hafez, and relegating uncultured amateurs. Against this effort to enforce an Egypt of high culture as envisioned by an elitist government, Simon asserts that “audiotapes and their users posed the single greatest obstacle to those tasked with securing the perimeters of public culture”. The masses loved sha’bi and through audiotapes, its vulgarity was spreading like wildfire.

According to Merriam Webster, vulgarity refers to a lack of cultivation and good taste. It can also mean morally crude, offensive in language, or plebeian. Bearing in mind that Egyptian conversations around vulgarity are held in Arabic, in which Simon translates vulgar as habit, sha’bi music ascribes to some of these definitions. It is of the common people, it might be considered crude, and one’s appreciation of it as an art form depends on one’s aesthetic preferences. However, sha’bi music, as well as mahraganat and Egyptian rap, displays a much higher level of linguistic sophistication and socio-historical consciousness than its critics admit.

Gorgeous lives upstairs and I live down below

Haba Fauq Haba Taht, Ahmed Adaweya 1974 (translation by Andrew Simon)

I looked up with longing, my heart swayed, and I was wounded

Oh people upstairs, go on and look at who is below

Or is the up not aware of who is down anymore?

Ahmed Adaweya, born Ahmad Muhammad Mursi on 26 June 1945, rose to fame with his hit al-Sah al-Dah Ambu (this title has no translatable meaning), recorded on an audiocassette in 1973. A controversial figure at the time, he earned himself a legacy as pioneer of sha’bi music and father to a lineage of working class musicians defying censorship and upper-class arrogance. “Contrary to the claims of some scholars, ʿAdawiya and other up-and-coming artists did not simply turn to cassettes […] as a practical solution for low-cost distribution and promotion,” writes Simon. “ʿAdawiya and his peers harnessed audiotapes, first and foremost, because Egyptian radio refused to broadcast what its officials deemed ‘vulgar’ material.”

Adaweya’s career is a great example of “the fluidity of vulgarity as a historical concept,” explains Simon. What was once considered unethical has recently resurfaced as progressive class commentary. “Vulgar material” could refer to lyrics talking about taboos like “Bent el-Geran”’s reference to smoking hashish and drinking wine, although the latter often appears in earlier Arabic poetry and was not considered vulgar then. It could also be understood as socially conscious, pointing to the fact that substance abuse in Egypt is double the international average. In the case of Adaweya, similar to Shakosh, those who felt offended by his promiscuous music were challenged by his groundbreaking popular success.

According to Simon, “annual figures published for 1976 accredit the performer with the top-selling cassette in all of Egypt”, significantly surpassing the country’s leading Qur’an reciter. By singing in a vernacular that was widely understood, about problems that ordinary Egyptians were facing, he struck a chord far louder than censorship could silence. He didn’t need to be legitimised by radio stations, his authenticity created his own grassroots mass following, and audio cassettes were his vehicle. Adaweya’s legacy continues to live on in mahraganat, one of the vulgar genres of our time. For example, Oka We Ortega’s 2017 hit “El3ab Yala” (Play, dude) mentions his song “Haba Fauq We Haba Taht”(A little bit up, a little bit down).

Welcome Father Nixon, O you of Watergate

“Nixon Baba”, Sheikh Imam 1974 (translation by Andrew Simon)

The day your spies welcomed you, they put on a great big show

In which the whores convulse and Shaykh Shamhuwrash [the devil; an allusion to Sadat] possesses the leader of the zar

As the parade continues an entourage of spiders creeps in order of their standing Round and round the never-ending mulid goes

O family of the Prophet, give us your blessings

Sheikh Imam (1918- 1995), born Muhammad Ahmad ‘Issa, was a working class singer and composer who made a living as a Qur’an reciter. His role as voice of the leftists, established through songs he performed in collaboration with vernacular poet Ahmed Fouad Negm, landed him in prison under both Presidents Nasser and Sadat. “Throughout Sadat’s rule, Imam’s tapes were not available in stores, kiosks, or on the streets”, writes Simon. “Instead, listeners manufactured them at a distance from soundproof professional studios. Egyptian universities, political demonstrations, social clubs, the artists’ apartment, and the homes of friends all served as spots to record Imam singing.

Imam never became a voice of the masses, but he is internationally remembered for his song “Nixon Baba” (Father Nixon), a counter-narration of President Nixon’s visit to Egypt in 1974. While official accounts hailed the event as the beginning of a new era in U.S.-Egypt relations, allegedly celebrated and welcomed by all Egyptians, Imam distributed his alternative, vulgar soundtrack. Simon explains, “In one verse, the song compares Nixon’s arrival to a zar, or a ceremony for excising spirits, in which the parade’s officials appear as spiders alongside convulsing whores. Sadat, the devil, possesses the woman responsible for vanquishing him and leads the theatrical show. Meanwhile, in a second verse, Nixon’s welcome assumes the form of a wedding procession, or zaffa. The American president plays the part of a groom, one married as a last resort, a pathetic figure on which Imam audibly spits.”

To this day, Imam’s version of the event endures, sometimes remixed into contemporary genres, his poetic vulgarity still speaking truth to the fact that many Egyptians thought Nixon’s visit a farce. As Simon writes, “Too often, scholars marshal cultural productions, whether in the form of films, novels, cartoons, poems, or countless other creative objects, only to illustrate what we already know about the Middle East and the region’s rich past. [..] In the case of Imam, conversely, we see how informal cassette recordings challenge what we think we know, or, in this instance, the Egyptian government’s “official story” of Nixon’s visit.”

The cassette tape turns 60 years old this year. In Egypt, it should be remembered as a vehicle for popular music to subvert censorship, undermine the walls erected by high culture, and create a new kind of independence. An independence of working class language and political thought that literally changed the sound of history. It popularised a kind of “vulgarity” that has been the soundtrack of Egypt for five decades, telling the stories of ordinary people and dancing on the nerves of those conservative men who continuously try and fail to mute Egypt’s sonic truths.

______________________________________________________________________

You can find Andrew Simon’s work under his Dartmouth profile and on Twitter. His next book will be a biography of Sheikh Imam, and he’d welcome any stories about the blind performer and political dissident that readers might wish to share.