“This mid twentieth century is Africa’s”, promised president Kwame Nkrumah at the historic All-African People’s Conference of 1958. Speaking in Accra to representatives from twenty eight African countries Nkrumah contemplated a `United States of Africa’ and forecast the next decade would belong to the continent. Just a year earlier The Gold Coast had become the first country in sub-saharan Africa to win independence from colonial rule, and 1960 would go down in history as The Year Of Africa as seventeen countries followed Ghana into self determination. And although Nkrumas’s United States of Africa would not come to pass – that Pan-African call to action would be heard and amplified in another United States…

In 1961 Blue Note Records released Jackie’s Bag by American saxophonist Jackie McLean which includes the composition `Appointment in Ghana.’ Musically the piece is a typical hard-bop workout but the choice of title was talismanic – an allusion to Africa that would be echoed through similar dedications by jazz musicians over the coming decade. It would be three years before President Lyndon B Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act ending segregation for Black Americans and many on Blue Note’s books would begin to draw inspiration from the African independence movement.

Founded in 1939 by Alfred Lion and Max Margulis, Blue Note’s first hit was a recording of “Summertime” by Sidney Bechet and by the end of the fifties the label was synonymous with the vanguard of jazz talent, the cool production of Rudy Van Gelder, and the iconic typography cover art of graphic designer Reid Miles. Key to the label’s success were also the sidemen Blue Note could call upon, and drummer Art Blakey would begin his long association with the label as such.

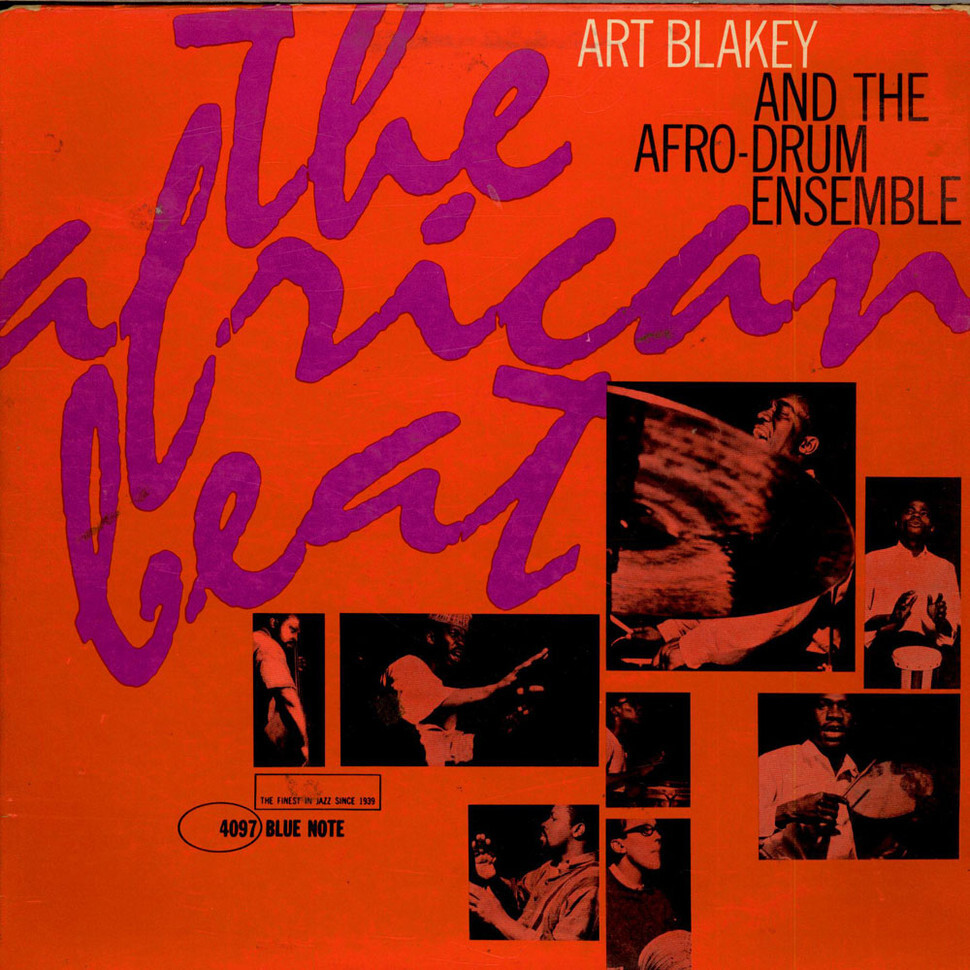

Art Blakey and the African Beat

Best known as the leader of the ever shifting Jazz Messengers, Blakey was born in 1919 and began his musical training in the Pentecostal Church. In common with many other jazz musicans Blakey would convert to Islam taking the name Abdullah Ibn Buhaina and spent a decisive year travelling in West Africa in 1948.

Jazz of course is an African diasporic music born in the cosmopolitanism of New Orleans, but Blakey’s trip is significant as it seems to have inspired him to dial more of the African influence back into the idiom. Although he would later tell Downbeat magazine: “I went to Africa because I couldn’t get any gigs. I went over there to study religion and philosophy”, Art Blakey nonetheless developed a distinctive style that borrowed from West African folkloric music and can be heard on his 1962 Blue Note album The African Beat.

Featuring Yusef Lateef on flute, sax, cow horn and thumb piano, alongside percussionist Chief Bey listed for “telegraph drum” (likely the West African Krin or log drum) the album opens with a recitation by Nigerian percussionist Solomon G Ilori.

An afrocentric set of tunes underpinned by polyrhythmic percussion and Yoruba linguistic references, Blakey can be heard employing techniques such as rapping on the shell of his drums and using his elbow to modulate the pitch of his toms thus making them speak like West African talking drums. Blakey was one of the first American drummers to add these tricks to his musical vocabulary and would bestow evocative African titles upon his compositions throughout his life as would many of his Jazz Messengers alumni.

Jazz and liberation

One such graduate of Blakey’s band who was also looking to Africa was trumpeter Lee Morgan who in 1966 released Search for the new land, the standout composition of which is “Mr Kenyatta” A homage to Kenya’s first president Jomo Kenyatta, the tune is a jaunty highlife influenced piece namechecking the anti-colonial activist who led Kenya to independence in 1963 and features a very clear use of the pan-African clave rhythm.

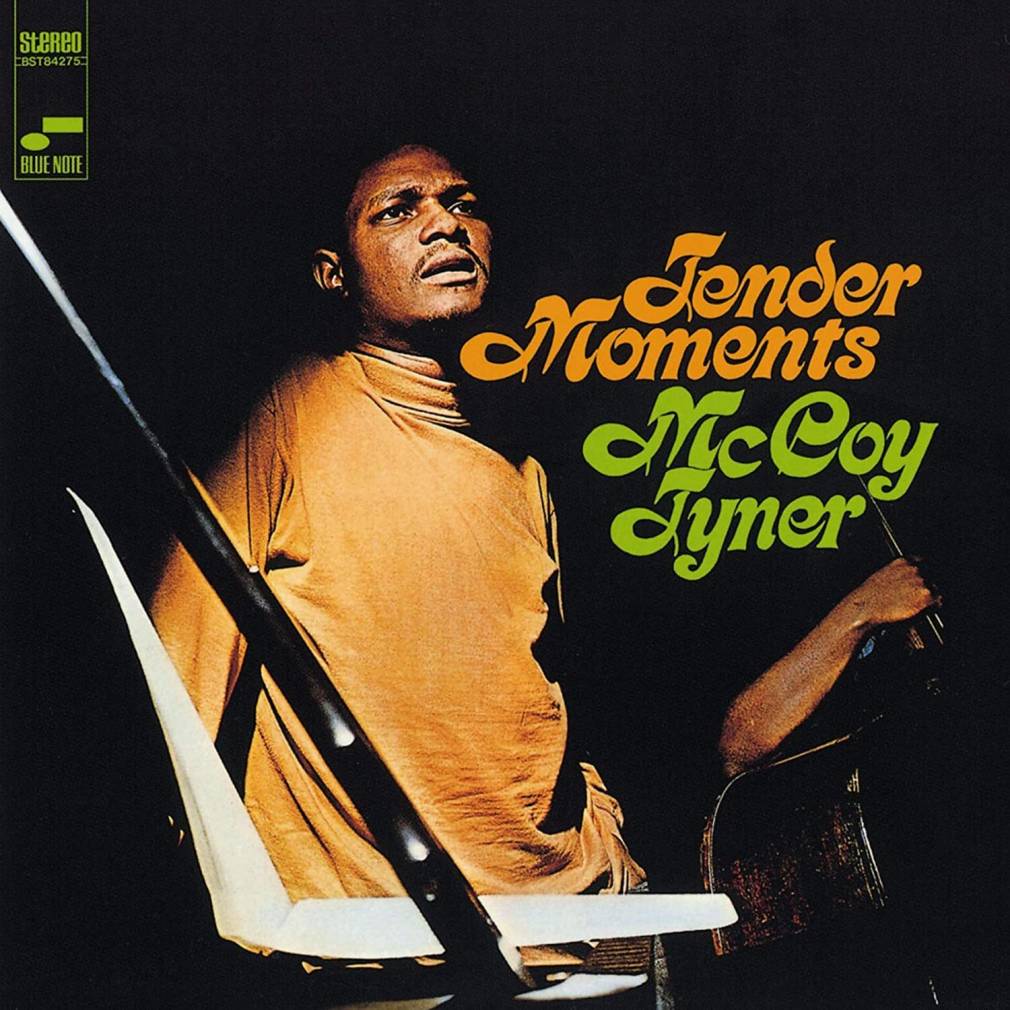

Yet another African statesman is suggested on McCoy Tyner’s “Man from Tanganyika”. A driving 6/8 tune from Tyner’s 1967 album Tender Moments, “Man from Tanganyika” features a Joe Chambers drum part which draws on the so-called `long bell’ – a family of bell patterns from the Gulf of Guinea here transposed onto a drum set. Tyner’s percussive ostinato piano contributes to an African feel as does the overblown flute, and though Tyner stated the `Man from Tanganyika’ was: “inspired by a fellow I knew who came from there” Tanganika’s man of the hour was Julius Nyerere – the teacher turned president and father of African socialism who led the country first as Tanganyika and then as Tanzania.

Other musicians who would reference new nations and borrow musical motifs for Blue Note include Wayne Shorter, Horace Silver, and as the sixties drew to a close – Trumpeter Donald Byrd whose lost album Kofi (only released by the label in 1995) is full of Ghanaian references. On an album that foreshadows Byrd’s explorations in jazz fusion – Donaldson Toussaint L’ouverture to give him his full revolutionary name (Byrd was named after the Haitian general who led the country’s revolution) included the tunes “Fufu” (pounded cassava) and “Elmina” (a point of no return during the transatlantic slave trade.)

So if America was looking to Africa, what were African jazz musicians up to?

African Jazz

This was the epoch of the big dance bands, often with a jazz suffix to their name. In Guinea state sponsored bands such as Bembeya Jazz National were created as part of the cultural policy of “authenticité. This policy encouraged and funded the revival of indigenous performing arts and in Guinea some forty orchestras and cultural troupes were created to tour West Africa. These ambassadors in turn inspired the governments of Mali, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Zaïre (as it was) to adopt similar cultural policy.

Bembeya Jazz who formed in 1961 were perhaps the most famous of these groups and recorded for the Syliphone label, a state funded enterprise and major African record label of the postcolonial era – Syliphone released eighty two records and seventy five singles.

Also providing a pan-African soundtrack to the decade were Franco’s OK Jazz, and Le Grand Kallé et L’african Jazz whose “Independence Cha Cha” released by the Belgian label Fonior became the unofficial Pan African anthem.

Meanwhile in South Africa pianist Abdullah Ibrahim and trumpet player Hugh Masekela would record the first full-length jazz LP by Black South African musicians released on Continental Records in 1960. Considered South Africa’s first important jazz band -The Jazz Epistles were inspired by Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and in their short association recorded just one now legendary long-player – Jazz Epistle Verse 1.

And so we can see that the discs produced on Blue Note during the sixties were part of a two way conversation between Africa and America. An enduring document to a time of Black renaissance, the oeuvre of artists such as Morgan and Tyner lionised the leaders we consider the elders of pan-Africanism today.