Inside a medieval castle and under the star-lighted sky of the Portuguese Atlantic coast, singer Oumou Sangaré and her musicians entertain a very mixed audience – in style, age and social class. At the same time behind the ramparts of the fortress, a mainly hippie youth crowd celebrates the Malian diva music in full hedonism, attending the show via two big screens and big sound systems. Some of them play percussions along the music, drinking homemade alcoholic beverage in a metallic mug, a must-have accessory during the week-long festivities in the streets of Sines. The former crowd bought a ticket for the show, while the latter have free access to the music, even if they stand far from the artist.

The “Festival of the Musics of the World” is a world in itself. More precisely, a “in mid-world”. Inside the castle overlooked by the donjon where Vasco de Gama was born – he the sailor and colonist of India – the main audience attends the “headliners” shows for between 10 and 20 €. There is a multi-generational crowd, and heterogeneous styles, a mix that creates a family-friendly and relaxed mood. Parents with kids stand next to young people smoking joints – yes, Portugal has decriminalized drugs possession and tolerated their consumption since 2000.

Behind the castelo‘s ramparts, another world. The one of those who can’t afford to pay for the ticket, or who’d rather enjoy what the festival has to offer for free. First, the broadcast of the shows on the big screens. Then the free shows on the huge scene located next to the beach, in a spectacular setting. And finally, the first three days in Sines and Porto Covo during which all the shows are free.

“GOING TO SINES” IN JULY HAS BECOME A MANTRA, AND IS A MANDATORY PILGRIMAGE FOR THOSE WHO LIKE THE “MUSICS OF THE WORLD”.

The overall free-of-charge character of the festival explains why Sines’ small village becomes this hippie camp for one week, temporarily inhabited by travelers, nomads, audacious bourgeois and utopian dreamers who, day and night on the medieval streets and on the ancestral sand, celebrate the ephemeral freedom to occupy the public space that public authority controls the rest of the time. A “enchanted interlude” that has been encouraged since 1999 by the tolerance of the city hall, the generosity of the festival team and the almost non-visibility of private sponsors (only five, amongst them three locals). “Going to Sines” in July has become a mantra, and is a mandatory pilgrimage for those who like the “musics of the world”.

(c) João Barbosa

If the name of the festival – Festival of the Musics of the World – may be embarrassing at first, it has a reason: it features music from the whole world. Just this year, around 40 countries were represented: Angola, Austria, Azores, Brasil, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Chile, China (Guangxi), Colombia, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, France, Greece, Guernsey, Haiti, Hawaii, Honduras (Garifana people), Indonesia, Inner Mongolia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Ivory Coast, Mali, Morocco, Mozambique, Nigeria, Peru, Puerto Rico, Portugal, South Africa, South Korea, Spain (Catalonia, Galicia), Syria, Tunisia (Djerid), Turkey, United Kingdom, United States of America, Yemen. But rather than territories delimited by borders that result from diplomatic negotiations, conflicts or colonization, this list represents musical cultures produced by encounters, cultural shocks or blends.

“The programme of FMM embraces and transcends the scope of world music”, the website reads. “It is open to folk, jazz, alternative music, fusion and urban music. More than just a world music or traditional roots music festival, FMM Sines strives to discover the music of the real world as it is made and experienced in our times: music marked by associations between performers from different geographic and cultural origins, arising from the movements of ideas and people which define contemporary society.” Would such an ambitious manifesto be successfully completed in the setting of a half-commercial festival with European/Western organization, scenography and localization? That is to say, on two big stages with a big sound system and light show, with crash barriers between the musicians and those who listen to them – this already sets the distinctive roles of artist and spectator.

(c) João Barbosa

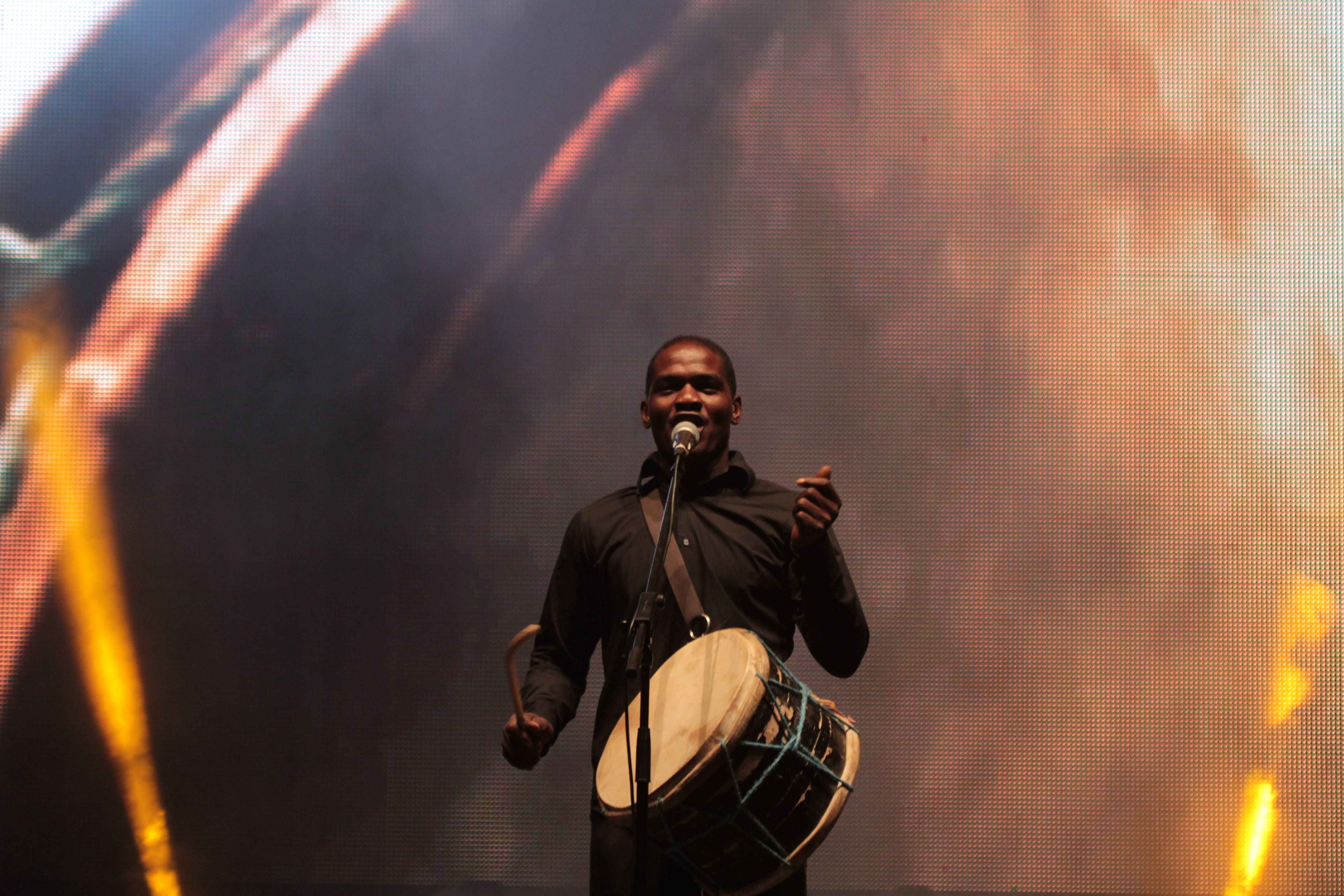

The musical offer is pretty rich, for sure. Just the African and Afro artists’ scope was large. The wassoulou chants and dances of Malian diva Oumou Sangaré, followed by her openly disciple Fatoumata Diawara, here performing in duo with her Moroccan friend Hindi Zahra. The stylish afrobeat of Brazilian orchestra Bixiga 70 – the name of one of São Paulo’s neighborhood – that accompanied great Nigerian saxophonist Orlando Julius, founder of modern afro-pop in the ’60s.

The refinement of the collaboration between Cameroonian bassist Richard Bona and Cuban orchestra Mandekan Cubano who paid tribute to the cabildos of the island’s slaves. The acoustic yet powerful songs of Aurelio Martinez, one of the few representatives of the culture of the Garifuna people, who populated the Afro-Caribbean coasts of Central America, and whose music echoes the Angolan sembas – until his voice, resembling Vum Vum’s – blended with the Spanish colonist’s influences. The Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latin blends from Colombia with La Mambanegra, Romperayo and Bulldozer – the latter being more urban and globalized. The reincarnation as a yoruba priest of Afro-American producer Ìfé and his electronic take on the Puerto Rican rhythmic heritage.

The post-punk avant-garde version of Brazilian candomblé by São Paulo trio Metá Metá. The reinvention of funaná by the radiant troubadour Mário Lúcio – the Cape Verdean version of Gilberto Gil – who also held the position of minister of culture, and collaborated with his Brazilian cousin.

(c) João Barbosa

The trance rituals of Tunisian banga – a ceremony of adorcism – by Ifriqiyya Électrique, a collaboration with French and Italian rockers [read our review of the album here]. The mystic trance of Bengali bâul chants and dances of Parvathy Baul, alone on stage with her ektara cordophone, her duggi drum and her nupur metallic anklets. The fervent preach drowned in blues, afrojazz and gospel by South African combo BCUC, champions of the liberation of the bodies and minds in a post-apartheid society, still segregated today. As an echo, Brazilian rapper Emicida‘s anti-racist messages and Tiken Jah Fakoly‘s spiritual and peaceful reggae.

All this variety, leaving aside non-African music, just as interesting. This richness puts FMM Sines in the category of Europe’s most eclectic festivals.

IF MUSIC IS A POWERFUL LANGUAGE AND A GREAT TOOL FOR SOCIAL AND CULTURAL LIBERATION IN TERRITORIES WHERE PEOPLE NEED TO FIGHT FOR IT, IT’S A TOTALLY DIFFERENT STORY WHEN IT COMES TO TRANSPOSE IT OUTSIDE OF THE COMMUNITY.

What about the objective to “discover the music of the real world as it is made and experienced in our times”? This is a very opportune idea today, when world music projects keep on reaching the European coasts, all conceived and shaped by the producers to please Westerners’ ears. Even in FMM Sines, a good amount of the artists seem to be shooting themselves in the foot, when playing the part of the “good colonized people”. They turned their music smoother for the big stages and audiences of the festivals, and they deliver peace and fraternity messages that ring hollow in front of such spectators already won over to their cause. Sometimes, it even sounds naive and simple. Even the big names fall into this trap: Tiken Jah Fakoly, BCUC (“Call a friend today and tell him you support him”), Oumou Sangaré, Fatoumata Diawara (“I sing for the children”), Mário Lúcio (“Let the children play, and the adults will stop waging war”).

(c) João Barbosa

If music is a powerful language and a great tool for social and cultural liberation in territories where people need to fight for it, it’s a totally different story when it comes to transpose it outside of the community. It tends to lose its value and is forced to mutate into a simpler and easier form for mainstream foreign audiences. This very trap is often conceived by the audience themselves, who were brought up with the idea that music creation can fit into a capitalist economic frame, the aptly named “music industry”.

When it comes to localized music practices with a strong and identified social function, their reception in festival with a distinctive artists / spectators scheme just come to a sudden end. It was the case for the banga trance of Ifriqiyya Électrique, who usually perform in the streets and people’s houses. This is a key ritual ceremony of adorcism for the Tunisian Djérid communities, used in case of diseases and weddings, to which all the inhabitants need to participate. But here in Sines on the big stage next to the beach, the musicians stand 2 meters above and 3 meters away from the crowd, while a big screen broadcast footage of the ceremonies that took place the precedent year in Africa, 2 000 km south of Portugal. When asked for their feedback during our interview, the Tunisian musicians used the term “show” to describe their performance, a word they say they never use for what happens inside their community. The same happened for Parvathy Baul’s mystic trance, who performed a ritual that belongs to the nomad Bengali minstrels, nicknamed “the mad” (“bâul”) and treated as outcastes. In order to earn their living they play in trains, in the streets and on the floor. The Indian woman’s performance in FMM Sines took place in a comfortable and modern auditorium with deep velvet armchairs, with no light but a focus on the musician, artificially turning the whole show into a dramatic moment.

IT REPRESENTS A SALUTARY INITIATIVE SO PEOPLE KEEP THEIR MINDS AND EARS OPEN TO MUSIC FROM THE WHOLE WORLD, AND A POSITIVE PATH TO TRY AND BREAK THE COLONIAL SYSTEM THAT THE WESTERN COUNTRIES CREATED FIVE CENTURIES AGO AND HAVE PATIENTLY IMPROVED UNTIL NOW.

It’s not that easy to escape the trap of world music when the artists travel far from their community or territory. So even if the festival offers “music with a spirit of adventure” – as their slogan reads – it can only show a musical snippet of why and how these rhythms and melodies were originally produced. Still, it represents a salutary initiative so people keep their minds and ears open to music from the whole world, and a positive path to try and break the colonial system that the Western countries created five centuries ago and have patiently improved until now. If one can acknowledge the fact that non-Western forms of culture still exist today and have survived centuries of oppression, we seem to be on the right path.

(c) João Barbosa

(c) João Barbosa

Photography by João Barbosa